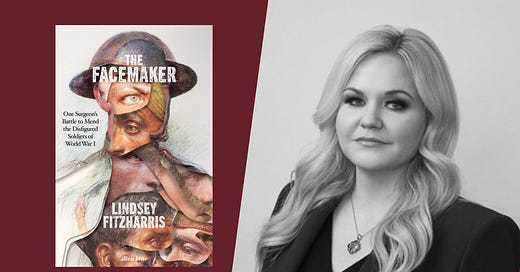

Lindsey Fitzharris: On Writing, Leaving Her Comfort Zone & Her New book...The Facemaker

Inside History Editor, Nick Kevern, talks to Dr Lindsey Fitzharris about her new book The Facemaker and much more...despite a few technological mishaps along the way.

(This article originally appeared in Inside History Issue 11)

The tech-savvy among us will immediately know the name of Lindsey Fitzharris. A social media icon of the historical world that has managed to bring new life to a profession that can often be accused of being quite stuffy. The image of the historian has certainly changed in the past decade and Fitzharris is one of those individuals who has helped to enable that. She is undoubtedly one of the most popular historians on Instagram whose feeds are full to the brim with the morbid and macabre. It might not be for those who with weaker stomachs but there are over 321,000 people who simply love it and I am one of those.

Despite her influence within this brave new world of technology, somehow we both struggled with the newfound delights of the Zoom conversation. Not that this is a bad thing, if anything it allows us to have some fun as we tried to get rid of the echo interfering with our interview.

A rich smile beamed across her face as the laughter continued. If anything, it felt like I was talking to an old friend rather than a best-selling author and television historian. It is impossible not to like her as more issues faced our chat.

Whilst I could see Lindsey clearly on my screen the same couldn’t be said from her side:

“Are you in a dark room? I can barely see you.”

Despite attempting to fix the lighting issues Lindsey could see me…but only just. More laughter followed about how it was going so far.

“I’ve got a feeling this is gonna be a great interview.” She said.

We were eight minutes in and we still hadn’t really started talking about her new book but in that time Lindsey said something that really stuck with me as she told me about the issues that come with promoting your new work to the world.

"It's all really intense right now. I've been doing interview after interview and it's just crazy so, but it's good. I mean, I shouldn't complain because a lot of authors don't get any interest in their books, so it's nice to be able to talk about it”.

She is right. With so many books published each year, some great books can easily become lost on the shelves to gather dust. No matter how talented you are as a writer, promotion is everything.

The Facemaker is her second book following her best-selling debut, The Butchering Art. For Fitzharris, The Facemaker has become the difficult second album that you often hear musicians talk of. It has been five years of painstaking research, and drafting but now it is finally ready for the world to see. Following up on something so successful and yet at the same time, moving away from your comfort zone in order to produce something fresh and exciting.

Storytelling is at the heart of her work. Don’t expect some dry, sterile history here. Her talent really excels in bringing that story to life and making her readers feel like they are there.

“For me, it’s always about the story,” She explains. “So my first book, The Butchering Art was about the surgeon Joseph Lister and Victorian surgery, the dawn of antiseptics and anaesthesia. This book is about World War I so I went into this knowing very little about it. This book The Facemaker is not a definitive history of anything, this is a particular story about one man at a moment in time. I knew a little about Gillies going into it and I knew enough to know that there was a really gripping story there about what war does to the human body and these amazing people who were really unsung heroes that stepped forward to help mend these bodies. It took me five years to write and research because I knew nothing about World War I. If you are out there and know nothing about World War I or never even thought about Military surgery then don’t worry, I was right there with you.”

Moving away from the Victorian era, Fitzharris has ventured into the 20th century, the First World War, and the pioneering surgeon, Harold Gillies. Gillies, the man who mended the faces of soldiers who were wounded by shrapnel, bullets, and everything else that the brutality of war could bestow on them. Their faces, their identity, and their resemblance to who they were before the fateful declaration of war in 1914 changed their lives forever.

She could have played it safe by sticking with the comforts of the 19th Century so why did Lindsey Fitzharris venture into unknown territory?

“Every decision I make is odd to people. At University I studied 17th-century alchemy so I’m an early modernist by training so when I wrote The Butchering Art my supervisor was like “Wow the 19th Century that’s so modern!” So now I’ve gone a step further into the 20th Century. But again it’s about the story that’s why I don’t call myself a historian first and foremost, although I am. For me, it’s about finding that way in so a general reader who knows nothing about the past, or maybe doesn't even like history, can pick the book up and fall into it and feel immersed in that period. I write narrative non-fiction, they read like novels if I’ve done a good enough job. I want to tell people what did it smell like? What did it feel like? What was it like to be in a World War I trench with your jaw blown off unable to scream for help?”

One of the things that always fascinates me is why people do what they do, particularly in the field of history. With the endless possibilities of the past, why would someone opt to pursue their specialisms?

So why did Lindsey become a medical historian? Because it's quite a niche and it's also quite gruesome and looking at her Instagram, well it's a bit gross.

“Haha, yeah it’s a bit much isn’t it Nick?”

“It can be yeah! But I was just wondering what inspired you to go into this field in the first place?

"I haven't actually got that question so far, so that's an interesting angle. Umm, you know, I always consider myself a storyteller, even as a little girl. My grandmother and I, would go from cemetery to cemetery hunting ghosts, and I guess I was a little bit obsessed with death and the macabre. But also, I was just really interested in the people who lived in the past. And knowing more about them and this interest in history flourished into something a bit more disciplined. So I ended up doing my master’s and my PhD at Oxford University, In the process of doing all the training. I got a little burnt out, intellectually burnt out, and so I began a blog called The Chirurgeons Apprentice, which I started because I wanted to fall back in love with history essentially and it was sort of meant to be little articles that form footnotes. Basically that in academic work, but these were little things that I would come across that I wanted to flesh out into bigger stories, and I wanted to teach people that medical history could be really interesting. I think that medical history's fascinating because even if you don't like history, you might like medical history because everybody knows what it's like to be sick, and in that way, it's very relatable. So what would happen if you had a toothache in 1792? Or what would happen if you had to have your leg amputated in 1846? And that's kind of what I do. I fill in that space, and I explain what that experience was like. That very human experience and how that kind of fear.”

Now knowing that Lindsey spent much of her time childhood combing graveyards in search of ghosts made me think about what kind of child Lindsey was growing up…I had to ask. I simply couldn’t resist.

“Very Weird! I’m sure a lot of my old school friends are not surprised by what I do for a living now.”

The weird young girl who roamed cemeteries with her grandmother has now grown up and found that many out there are just as interested in the things she is interested in. Her work in showing us the importance of medical history might seem macabre but it is also endlessly fascinating.

Her new book, The Facemaker, is a testament to exactly that sentiment. The brutal injuries that the soldiers faced and their own stories are at the centre of her book. Of all the thousands of stories she could have chosen to highlight, there is one in particular that struck a chord. His name was Private Percy Clare.

"The book begins with Private Percy Clare who gets shot in the face in 1917 during the Battle of Cambrai. The reason I chose him was because he wrote this amazing detailed diary about his experiences in such a way that I hadn't come across with some of Gillies's other patients. Some did write about their experiences or give oral interviews but Clare really went into detail and wrote so beautifully. But the challenge with him was that he was injured in 1917 so the prologue opens with this really harrowing scene of him getting shot and trying to get off the battlefield which was a huge challenge. Then I had to dial the clock back to right before the war so that in Chapter One you meet Harold Gillies who was ultimately the man who was going to solve this problem for a lot of these men who were injured in the face during this time. Obviously, Gillies had hundreds of thousands of patients and I chose a handful of patients to tell this story. The ones who really stood out to me. because I don't want to overwhelm the readers with too many men's stories but I thought that this book is not just about one man, The Facemaker, but about many men and I think that the cover that Penguin has created really captures that idea."

Despite the book's subtitle, collaboration was at the heart of everything that Gillies did. This was not just one man's story and Fitzharris is keen to highlight not only the collaborative element of his work but also the creative aspect.

"One of things that Gillies really brought to the table that other surgeons who were working during World War I weren't doing was a really collaborative approach. So he brings artists on board in the form of Henry Tonks, he brings dentists on board. A lot of times surgeons saw dentists as inferior so they didn't necessarily work with them. But the dental surgeons were really important to the facial reconstruction process. He brought in X-ray technicians so there were all kinds of people who ultimately worked together in this very creative process to rebuild soldiers' faces."

World War I changed the technological scene in terms of warfare but as Fitzharris explains, it also changed the medical world.

"The medical community was really taken aback at first. The sheer number of people requiring help but also the nature of their injuries. So this drove a lot of these medical advances in a very short period of time between 1914 and 1918."

For medical history and medical historians, war has helped our understanding of not just the human aspect of conflict but also our ability to adapt. It is also important to fail and more importantly, to learn from it.

Trial and error is also the common scourge of the writer as they redraft their work and take their time. The world has been waiting patiently for Fitzharris's new book and there is no denying that Fitzharris is a writer who is passionate about what she does. For the reader, patience is a virtue. A delayed gratification of sorts that makes this release all the sweeter.

"For every story that I tell to tell I am generally passionate about. Which is why it can take me five years to finish a book but I hope that the end result is worth it."

I kept thinking back to little Lindsey and her grandmother. How the love of storytelling began in those cemeteries of Middle America and how they have grown, matured, and blossomed. No matter how odd you think you might be at the time, you simply view the world differently from others. Then over time, you realise that you are not alone and that there are still many more cemeteries to explore.

The gravestone would read: "Here lies our past and the stories of those who were there before us". Buried beneath are the mortal remains of hope, love and the remains of the extraordinary lives of those waiting for someone to bring their history to life. Thankfully a young Lindsey Fitzharris did exactly that and as she got older, continues to do so.

The story of Harold Gillies, those who worked with him, and the patients he helped throughout, and even after The Great War, is a fascinating one and thankfully it was a cemetery an older Fitzharris explored and brought back to life in the only way she knows how. Through the art of storytelling. Her admiration for Harold Gillies resonates throughout, not only in the book but during our entire interview. Perhaps he might have even thought of himself as a bit odd at times whilst reconstructing the faces of soldiers.

We need these people and we need the likes of Lindsey Fitzharris to bring these people back to life. Never worry about being different, weird, or odd...embrace it.

The Facemaker: One Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I is out now in Hardback and Paperback. You can purchase your copy here.

(By clicking the link you will be directed to Amazon. Any purchase will result in a small commission for Inside History)

I admit, I've never given much thought to this subject. I applaud Fitzharris for her deep-dive research. Thanks for sharing this fascinating interview.